SKC Films Library SKC Films Library |

| SKC Films Library >> Science >> Physics >> Biography |

Joseph

Fraunhofer Joseph

Fraunhofermaker of some of the most perfect optical lenses and prisms ever made Joseph Fraunhofer was born in Straubing, Bavaria (now part of Germany), on March 6, 1787, the son (and grandson) of a talented but poor glassmaker. Orphaned by age 11 and apprenticed to a looking-glass maker in Munich, he was prevented from getting a formal education by both money and the requirements of his apprenticeship master. Although he had inherited his father's skill at glassmaking, Joseph's master used him more like a slave than a gifted student and was so harsh in his treatment of him that the youngster was at one time in danger of starving to death. Fraunhofer's fortunes changed dramatically in 1801, however, when the ramshackle building in which he lived and worked collapsed, trapping him in the ruins. A huge crowd watched for hours while rescuers made their way into the rubble, and were elated when both Joseph and his master finally emerged unhurt. One of the persons watching the operation was Prince Elector Maximilian Joseph IV, who was so moved by the boy's situation that he furnished him with books and money and forced his employer to give him time for study. Although Fraunhofer's employer initially followed the Prince's orders and allowed his apprentice to read his books, he also resumed his former practice of using him more like a slave than an apprentice. By 1806 Fraunhofer had determined that his master had no intention of actually allowing him to study glassmasking and he used some of the money the Prince had given him to buy out his apprenticeship contract. That same year, Joseph von Utzschneider, owner of the Munich Optical Institute (a private business that made scientific instruments and conducted optical experiments) and a good friend of the Prince, made him a member of the Institute's staff. Fraunhofer's skill at making optical lenses and optically perfect prisms was quickly appreciated by Utzschneider, and he was made a full partner with Utzschneider in 1809. Before long, lenses and prisms produced by the Institute were being used by scientists and research institutions across Europe. Already a naturally talented glassmaker, Fraunhofer developed new grinding techniques that allowed him to create some of the most perfect optical lenses and prisms ever made. He also invented a polishing machine and an improved polishing material, improved the composition of the cement used to assemble lenses, and introduced the use of an unaltered sheet of glass as a test device to check the shape and concentricity of polished lens surfaces. Under the tutelage of Pierre Louis Guinand, a Swiss glass technician, Fraunhofer developed a type of glass especially suited to the making of thicker and larger lenses. In 1817, he used his new glass to make a 9.5-inch object lens for the Russian Dorpat Observatory in Estonia that, after being placed in the observatory's telescope, allowed astronomers to identify over 2,000 new stars within a few years.

(right: a solar spectrum similar to that seen by Fraunhofer)

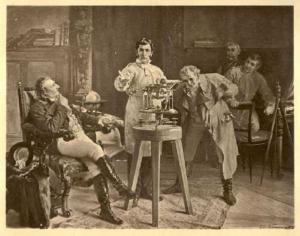

(left: Fraunhofer demonstrating his spectroscope) In 1824, Fraunhofer was honored for his contributions to the Bavarian glassmaking industry by being knighted. He was never able to fully explore the scientific potential of his many discoveries, however, as he contracted tuberculosis and died on June 7, 1826. Although Fraunhofer was well respected for his lens- and prism-making skills in his day, his scientific work was largely ignored because he refused to publish any of his methods (he saw himself as an artisan and his methods as a trade secret). PRINT SOURCE WEB SOURCE SEE ALSO |

| SKC Films Library

>> Science >> Physics >> Biography This page was last updated on 06/06/2017. |