SKC Films Library SKC Films Library |

| SKC Films Library >> Religion and Mythology >> Evangelism and Revivals |

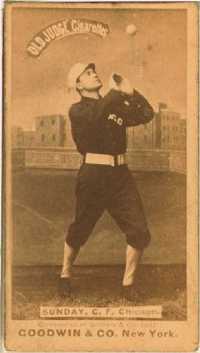

| Billy Sunday baseball player-turned evangelist William Ashley Sunday was born in Ames, Iowa, on November 19, 1862. His father died just five weeks after his birth, so Billy and his older brother were subsequently raised in the home of their grandparents and at the Soldier's Orphans Home because their mother was too impoverished to care for them. By the age of 14 Sunday was fending for himself, and in 1880 he moved toMarshalltown, Iowa, where he joined a fire brigade, worked at odd jobs, and played for the town baseball team. Baseball Career In 1883, Adrian "Cap" Anson, a Marshalltown native who was then playing for the Chicago White Stockings, convinced team owner A.G. Spalding to sign fellow Marshalltown resident Billy Sunday. Sunday made his major league debut on May 22, 1883, and struck out all four times he went to the plate. He subsequently struck out nine more times before finally getting a hit (in his fourth game), but his ability in right field was enough to keep him on the team. Once he began getting hits, he also proved to be fast on the basepaths and earned a reputation for being a quite capable base stealer. During his first four seasons with Chicago, Sunday was a part-time player, only coming into the game to take Mike "King" Kelly's place in right field when Kelly served as catcher. In 1887, when Kelly was sold to another team, Sunday became Chicago's regular right fielder, but an injury limited his playing time to fifty games. Although he was never a stellar player, Sunday's personality, demeanor, and athleticism made him popular with the fans, as well as with his teammates. Billy Sunday baseball card from his White

Stockings years In the winter of 1887 Sunday was sold to the Pittsburgh Alleghenys, for whom he played as starting center fielder in the 1888 season (the first full season of his career). He was among the leaders in stolen bases that season, with 71. In 1890, a labor dispute led to the formation of a new league, composed of most of the better players from the National League. Although he was invited to join the competing league, Sunday's conscience would not allow him to break his contract with Pittsburgh. Sunday was named team captain, and he was their star player. By August of 1890 the Alleghenys were no longer able to meet their payroll, and Sunday was traded to the Philadelphia Phillies for two players and $1,000 in cash. In March 1891, Sunday requested and was granted a release from his contract with the Philadelphia ball club (he had played his last game on October 4, 1890). In the days before outfielders wore gloves, Sunday was noted for thrilling catches featuring long sprints and athletic dives, but he also committed a great many errors. He was best known as an exciting base-runner, regarded by his peers as one of the fastest in the game, even though he never placed better than third in the National League in stolen bases. He ended his baseball career with a .248 batting average, 12 home runs, 170 RBI's, and 246 stolen bases. Although he left baseball for an evangelical career, Sunday remained a prominent baseball fan throughout his life. He gave interviews and opinions about baseball to the popular press, and frequently umpired minor league and amateur games in the cities where he held revivals. Evangelical Career On a Sunday afternoon in Chicago during the 1886 baseball season, Sunday and several of his teammates were out on the town for their day off when they stopped to listen to a gospel preaching team from the Pacific Garden Mission. Sunday subsequently began attending services at the mission, where he was converted to Christianity, after which he began attending the Jefferson Park Presbyterian Church, a congregation handy to both the ball park and his rented room. It was at Jefferson Park that Sunday met Helen Amelia "Nell" Thompson, daughter of the owner of a Chicago dairy business. The couple had to overcome her father's strong objections to Sunday's career, but were finally able to get his blessings and were married on September 5, 1888. The couple subsequently had two children, Helen and George. In 1891, Sunday turned down an offer of $500 a month to sign with Cincinatti and took an $83-a-month job as "secretary of the religious department" for the Chicago YMCA instead. For three years Sunday visited the sick, prayed with the troubled, counseled the suicidal, and visited saloons to invite patrons to evangelistic meetings. In 1894 he was offered $2,000 a month to play for Pittsburgh, but took a job as advance man for evangelist J. Wilbur Chapman at $40 a week instead. When Chapman suddenly decided to leave the evangelical circuit for a permanent pulpit in 1896, Sunday took his place on the circuit. He held his first revival meeting at Garner, Iowa, in January of 1897. For the next twelve years Sunday preached in approximately seventy communities, most of them in Iowa and Illinois. Towns often booked Sunday meetings informally, sometimes by sending a delegation to hear him preach and then telegraphing him while he was holding services somewhere else. He was ordained as a Presbyterian minister in 1903, and by 1905 was doing well enough on the circuit to hire his own advance man. Sunday often took advantage of his reputation as a baseball player to generate advertising for his meetings. In 1907, for example, he organized Fairfield, Iowa, businesses into two baseball teams and scheduled a game between them. He then came dressed in his baseball uniform and played on both sides. He was also not above resorting to pure gimmicks to attract people, including the hiring of a circus giant as an usher. But it was Sunday's preaching style that provided his best advertising. He used his whole body in his sermons, as well as nearby objects, such as his chair, which he would sometimes fling around while preaching. He also became the master of the one-liner, which he would use to clinch his practical, illustration-filled sermons. One of his most famous was "Going to church doesn't make you a Christian any more than going to a garage makes you an automobile." illustration of a Billy Sunday revival Unusual for evangelical preachers of the day, Sunday was known for addressing social issues with as much vigor as religious ones. He supported women's suffrage, called for an end to child labor, and included blacks in his revivals, even when he toured the deep South. On evolution, however, he walked a very fine tightrope by supporting neither evolution nor a strict Genesis version of creation. In 1908, Nell Sunday decided to take over management of her husband's revival campaigns. Leaving the children in the care of a nanny, Nell soon turned Sunday's "out-of-the-back-pocket" organization into a national phenomenon. By 1910, Sunday was conducting meetings lasting a month or more in small cities like Youngstown, Wilkes-Barre, South Bend, and Denver. By 1915 he was holding meetings in New York City, Philadelphia, Kansas City, and other major cities. During that period the Sundays also hired a staff of musicians, custodians, advance men, and Bible teachers. The most significant of these new staff members were Homer Rodeheaver, an exceptional song leader and music director who worked with the Sundays for almost twenty years, and Virginia Healey Asher, who (besides regularly singing duets with Rodeheaver) directed the women's ministries, especially the evangelization of young working women. During the 1910s, Sunday was front page news in the cities where he held campaigns. Newspapers often printed his sermons in full, and during World War I, local coverage of his campaigns often surpassed that of the war. Sunday was the subject of over sixty articles in major periodicals, and he was a staple of the religious press regardless of denomination. After World War I (which he raised millions of dollars to support), Sunday's influence began to decrease. Radio, movies, and other forms of entertainment drew masses away from the preacher, though he never lacked for speaking engagements. The Sundays' daughter died of what is believed to have been multiple sclerosis in 1932, and their son committed suicide in 1933. Billy Sunday collapsed while preaching in Des Moines in 1933, and died of a heart attack on November 6, 1935; he is buried in Forest Home Cemetery, Forest Park, Illinois. SOURCES SEE ALSO |

| SKC Films Library >> Religion

and Mythology >> Evangelism and Revivals This page was last updated on May 22, 2017. |