SKC Films Library SKC Films Library |

| SKC Films Library >> American History >> United States: Local History and Description >> Gulf States >> Mississippi River and Valley |

Henry

Miller Shreve Henry

Miller Shrevedesigner of a steamboat suited to the relatively shallow water of the Mississippi River, and of a steam-powered boat specially outfitted to clear snags from river channels Henry Miller Shreve was born in Burlington County, New Jersey, on October 21, 1785. He was the fifth of eight children born to Isaiah and Mary Cokely Shreve, and also had four half-siblings from his father's first wife. His father moved his large family to Brownsville, Pennsylvania, in 1788, onto land he bought from George Washington, and Henry spent his youth in the area between the Youghiogheny and Monongahela rivers. After his father died in 1802, Henry hired onto a flatboat crew to help support the family, and he knew from that point he would spend the rest of his life on the water. In 1807, Shreve built a keelboat and started a lucrative fur trade between St. Louis, Missouri, and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. In 1810, he expanded his business by negotiating a deal with the Sauk and Fox Indians on the Galena to carry lead from their mines to New Orleans. He married Mary Blair in 1811, and the couple ultimately had three children; the children were raised almost exclusively by their mother, as Henry as away from home on business as much as he was home.

Although his steamships were successful, Shreve could not expand his business because the Robert Fulton-Robert Livingston partnership had been given a monopoly on government contracts for shipping via steamboat on the Lower Mississippi. A series of legal battles finally broke that monopoly in 1817, and the imposition of any new similar monopolies was ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in 1824, via Gibbon v. Ogden.

In 1833 Shreve began working on his largest project to date, the "Great Red River Raft" in Louisiana, a logjam on the Red River between Baton Rouge and present-day Shreveport that had been created by decades of channel neglect and an accumulation of bank cave-ins that had felled entire stands of trees into the river. The logjam was so great in some areas that new trees had actually been able to take root in the middle of the channel. It took him five years, but Shreve's snag boats accomplished the mission, and, during the process, speculators named their new town Shreveport as a show of gratitude for his work. In 1841 the new Whig administration of William Henry Harrison-John Tyler wanted to rid the federal government of Jacksonian appointments, and Shreve was "asked" to step down from his position. He subsequently moved to St. Louis, Missouri, and took up farming. He also tried to get the federal government to compensate him for the use of his snag boats, but was unsuccessful. Mary died in 1845, and, in 1847, he married Lydia Rodgers, with whom he had two daughters. His last daughter was born in 1849, but died in January of 1851; he also lost two grandchildren that winter, and the quick succession of personal losses took a toll on his health, which had already been compromised by a harsh winter. He died in St. Louis on March 6, 1851, and was buried in that city's Bellefontaine Cemetery. In 1986, Shreve became one of the first inductees into the National River Hall of Fame in Dubuque, Iowa, along with author Samuel Clemens (aka Mark Twain). WEB SOURCES SEE ALSO |

| SKC Films Library >> American History >> United States: Local History and Description >> Gulf States >> Mississippi River and

Valley This page was last updated on June 16, 2017. |

Like many others who

lived along the Ohio River, Shreve had seen how

Like many others who

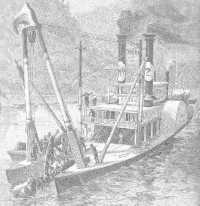

lived along the Ohio River, Shreve had seen how  On January 2,

1827, Shreve was named Superintendent of Western River

Improvements. One of his first tasks was to clear the

Ohio and Mississippi rivers of obstructions, for which he

designed The Heliopolis (at right), a steam

"snag boat" constructed of twin 125-foot hulls

connected by a series of beams and fitted with various

contraptions for clearing snags from riverbeds, including

rams and hoists; it even had an on-board sawmill to

dispose of trees if necessary. The Heliopolis

had both rivers cleared of snags by 1829, after which he

began working on the Arkansas River. In 1832, Congress

appropriated $15,000 to clear the Arkansas, and specified

the necessity of using Shreve's "snag boats"

for the task. Using two snag boats, three machine boats,

and a steamboat, Shreve cleared the Arkansas from Pine

Bluff to Little Rock, Arkansas, in about a year.

On January 2,

1827, Shreve was named Superintendent of Western River

Improvements. One of his first tasks was to clear the

Ohio and Mississippi rivers of obstructions, for which he

designed The Heliopolis (at right), a steam

"snag boat" constructed of twin 125-foot hulls

connected by a series of beams and fitted with various

contraptions for clearing snags from riverbeds, including

rams and hoists; it even had an on-board sawmill to

dispose of trees if necessary. The Heliopolis

had both rivers cleared of snags by 1829, after which he

began working on the Arkansas River. In 1832, Congress

appropriated $15,000 to clear the Arkansas, and specified

the necessity of using Shreve's "snag boats"

for the task. Using two snag boats, three machine boats,

and a steamboat, Shreve cleared the Arkansas from Pine

Bluff to Little Rock, Arkansas, in about a year.