SKC Films Library SKC Films Library |

| |

| SKC Films Library >> American

History >> United States:

General History and Description

>> Revolution

to the Civil War, 1775/1783-1861

>> Middle

19th Century, 1845-1861

>> Individual

Biography, A-Z |

| Charles Sumner long-time member of the U.S. Senate who was so popular with his constituents that he was re-elected despite being unable to serve

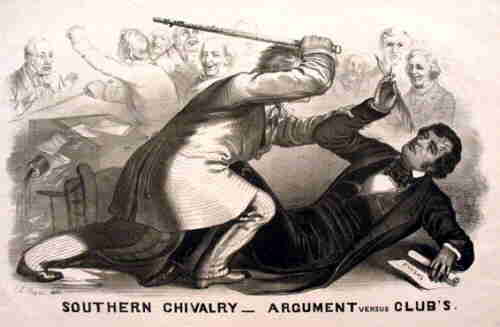

Charles Sumner was born in Boston, Massachusetts, on January 6, 1811. He attended the Boston Latin School, graduated from Harvard College in 1830 and the Harvard Law School in 1833, was admitted to the bar in 1834, and commenced the practice of law in Boston. He lectured at the Harvard Law School from 1836 to 1837, and then spent three years traveling Europe before once again settling down to his Boston law practice. Sumner was a reform-minded individual from almost the very beginning of his career. He worked with Horace Mann for the improvement of the system of public education in Massachusetts. Prison reform and peace were other causes to which he gave his early support. In 1846, Sumner declined the Whig Party nomination for election to the U.S. House of Representatives. In 1848, when the Whig Party nominated Zachary Taylor, a slave-owning Southerner, for the presidency, Sumner took an active part in organizing the Free-Soil Party. As a Free-Soiler, he was a candidate for the House that same year, but was defeated. In 1851 control of the Massachusetts Legislature was secured by the Democrats in coalition with the Free-Soilers, but the Democrats refused to vote for Sumner, the Free-Soilers' choice for the U.S. Senate. A deadlock of more than three months ensued, finally resulting in the election (on April 24) of Sumner by a majority of a single vote. He was re-elected as a Republican in 1857, 1863, and 1869, and served from April 24, 1851, until his death. In the closing hours of Sumner's freshman session (on August 26, 1852), despite strenuous efforts to prevent it, Sumner delivered a speech, "Freedom national; Slavery sectional," which marked a new era in American history. On May 20, 1856, Sumner delivered his "Crime Against Kansas" speech, in which he denounced the Kansas-Nebraska Act as being "in every respect a swindle," and held its authors, Stephen A. Douglas and Andrew P. Butler, up to the scorn of the world. Two days later, Preston S. Brooks, a Congressman from South Carolina and relative of Butler, confronted Sumner in the Senate chamber, denounced his speech as a libel upon his state and upon Butler, and then proceded to beat Sumner with a cane (left). The injuries inflicted upon Sumner by Butler were so severe that Sumner was unable to retake his seat in the Senate until December, 1859. During his three-year absence from the Senate, the Legislature of Massachusetts continued to re-elect Sumner, in the belief that his vacant Senate chair was the most eloquent pleader for free speech and resistance to slavery.

After the Southern Senators left the Senate in 1861, Sumner was made chairman of the Committee on Foreign Relations. While the Civil War was in progress his letters from political leaders in England were read by Sumner to the Cabinet, providing President Abraham Lincoln and his advisers with an intimate account of British political thought in regards to the war. Sumner saw himself as a special champion of Negroes, being one of the most vigorous advocates of emancipation, of enlisting blacks into the Union Army, and of the establishment of the Freedmen's Bureau. And, he truly believed that the credit or blame for imposing equal suffrage rights for blacks upon the South as a condition of reconstruction rested with him. During the impeachment proceedings against President Andrew Johnson, Sumner was one of Johnson's most implacable assailants. Sumner's opposition to President Ulysses Grant's scheme for the annexation of Santo Domingo (1870), led to his being deposed from the chairmanship of the Committee on Foreign Relations, in 1871. In 1872, Sumner introduced a resolution providing that the names of battles with fellow citizens should not be placed on the regimental colors of the United States. The Massachusetts Legislature denounced the resolution as "an insult to the loyal soldiery of the nation" and as "meeting the unqualified condemnation of the people of the Commonwealth." Sumner was censured, but the censure was eventually annulled, in early 1874. On March 10, 1874, against the advice of his physician, Sumner went to the Senate -- it was the day on which the resolution to annul the censure was scheduled to be presented. That night he was stricken with an acute attack of angina pectoris, and he died the following day. After laying in state in the Capitol Rotunda, he was interred in Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, Massachusetts. INTERNET SOURCE SEE ALSO |

SKC Films Library >> American History >> United States: General History and Description >> Revolution to the Civil War, 1775/1783-1861 >> Middle 19th Century, 1845-1861 >> Individual Biography, A-Z This page was last updated on March 10, 2017. |