SKC Films Library SKC Films Library |

| SKC Films Library >> American History >> Indians of North America >> Wars, Battles, Etc. |

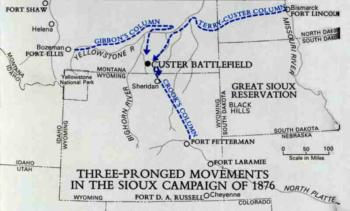

| Battle of the Little Bighorn "Custer's Last Stand" Background and Prelude In 1875, Lakota war chief Sitting Bull had a vision in which it was revealed that all of his enemies would be delivered into his hands. That same year, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs decreed that all Lakota not settled on reservations by January 31, 1876 would be considered hostile. In March 1876, Sitting Bull called a "meeting" of Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho chiefs at his camp on Rosebud Creek in Montana Territory. During the meeting he led a sun dance and told the assembled chiefs and warriors that they must change their way of fighting -- instead of showing off to prove their bravery, they should fight to kill, otherwise they would lose all their lands to the whites. At the same time, military authorities were organizing a campaign to force the Lakota and their allies onto reservations. On May 17, 1876, a column consisting of twelve companies of the 7th Cavalry, two companies of the 17th Infantry, and the Gatling gun detachment of the 20th Infantry, all led by Brigadier General Alfred Terry, departed westward from Fort Abraham Lincoln in the Dakota Territory. Another column, led by Brigadier Genrtal George Crook and consisting of ten companies of the 3rd Cavalry, five of the 2nd Cavalry, two of the 4th Infantry, and three of the 9th Infantry, moved north from Fort Letterman in the Wyoming Territory on the 29th. A third column, consisting of six companies of the 7th Infantry and four companies of the 2nd Cavalry and led by Colonel John Gibbon, marched east from Fort Ellis in western Montana Territory on the 30th. The plan was for the three columns to join up near Sitting Bull's encampment and attack as one main army. map showing the general movement of the three army

columns that converged at the Little Bighorn The Army's plan began to fall apart on June 17, when Crook's column found itself engaged in battle with warriors led by Crazy Horse, an Oglala Lakota chief who had been inspired by Sitting Bull's words, at Rosebud Creek. Finding themselves hopelessly outnumbered, Crook's men were forced to retreat and regroup, delaying their rendezvous with the other two columns, which joined up near the mouth of the Rosebud River. On June 22, General Terry ordered the 7th Cavalry, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel George A. Custer, to begin a reconnaissance and pursuit along the Rosebud, while the rest of the united forces marched toward the mouth of the Little Bighorn. Terry's plan called for all of the units to converge on and attack the Lakota encampment on the 26th or 27th, but Custer engaged the enemy sooner than anticipated, and "Custer's Last Stand" was the ultimate result. The Battle Early in the morning of June 25, Custer's scouts reported seeing signs of a Native American village on the opposite side of the Little Bighorn River, about 15 miles in the distace. Custer originally planned to attack the village on the morning of the 26th, but when he learned that several hostiles appeared to be following his troops he decided to attack without delay. He divided his twelve companies into three batallions -- three companies under Major Marcus Reno were to approach the village from the south, three under Captain Frederick Benteen were to prevent escape through the upper valley, and the rest, directly under Custer, were to attack from the north. The three batallions began their approach at noon, and, believing the village to be inhabited by a few hundred women, children and old men, expected the battle to be brief. map showing how Custer divided his forces Reno's force crossed the river around 3 pm and advanced toward the southern end of the village. When they began firing into the village, mounted Cheyenne and Sioux warriors began streaming out to meet the attack. Within ten to fifteen minutes it was obvious that Reno's men were outnumbered by about five to one, and Reno ordered a retreat into the timber along the river. When the Indians set fire to the timber, Reno "authorized" a retreat back across the river toward bluffs on the other side. Reno's troops were soon joined by Benteen's column, which just happened to be on a lateral scouting mission at the time, and the combined forces were able to fend off continued Indian attacks for the rest of that day and most of the next. Reno and Benteen were finally "rescued" when the rest of General Terry's troops arrived at the Little Bighorn on the 26th. The fates of Custer and his men, however, would not be learned until later that day. While Reno and Benteen were fighting for their lives on the bluff, Custer's force of about 210 men had engaged the Lakota and Northern Cheyenne about 3.5 miles to the north. Although no contemporary account of the battle itself exists, Crazy Horse had apparently crossed the river downstream and, with a force possibly numbering over a thousand, had surrounded Custer's force. Custer's men were cut down as they tried to retreat to higher ground to the north, as evidenced by the fact that bodies were found in an almost straight line leading up to the hill upon which Custer made his last stand. Evidence of organized retreat and resistance included apparent breastworks made of dead horses, the bodies of dozens of warriors, and the fact that most of the soldiers had been killed while still in formation (as evidenced by the positions and groupings in which the bodies were found). By the time Terry's troops arrived at the battlefield, most of the dead had been stripped of their clothing and many had been ritually mutilated. Custer 's body was found near the top of a hill; it had not been mutilated, presumably because he was wearing buckskins instead of a uniform and was therefore not seen as important by Crazy Horse. one of many depictions of Custer's

Last Stand Casualties The total number of Native American casualties has never been determined, with estimates ranging from as few as 36 to as many as 300 or more. The 7th Cavalry suffered 16 officers and 242 soldiers killed, and 1 officer and 51 soldiers wounded, between the 25th and 26th of June. Every soldier and officer in the five companies with Custer was killed. When Terry's men first surveyed the final battlefield they found no evidence of survivors, but a few days later one lone horse came wandering into Terry's camp. It was soon determined that the horse belonged to Captain Myles Keogh, who had been killed alongside General Custer. Although Comanche had been wounded and was obviously weak, he went down in history as the sole survivor of Custer's Last Stand (although, in fact, many other horses also survived the battle).

SOURCES SEE ALSO |

| SKC Films Library

>> American History

>> Indians of

North America >> Wars, Battles, Etc. This page was last updated on 05/26/2017. |